Nov 19th 2025

Markus Rudolph

Language execution with Langium and LLVM

In this blog post, we continue exploring the synergy between Langium and LLVM by detailing how to generate LLVM IR from an AST created by Langium to make your language executable.

Eclipse Langium has proven to be a highly valuable and reliable framework for creating domain-specific languages. Since its inception in 2021, we’ve seen numerous projects succeed with the help of its flexibility and modern tooling approach. The same is true for Eclipse Xtext, which served as our standard language engineering toolkit in the 2010s, when Java was still the leading platform for domain-specific tooling.

Both frameworks can be adapted to provide excellent tooling for the vast majority of language projects. Still, there are a few cases where we’ve hit hard limitations — most visibly in long response times for editor features such as completion, validation, and other LSP capabilities.

In this article, we distill the key observations from our work with both frameworks and share something exciting: the initial steps toward a new language framework built for the next class of performance-intensive use cases.

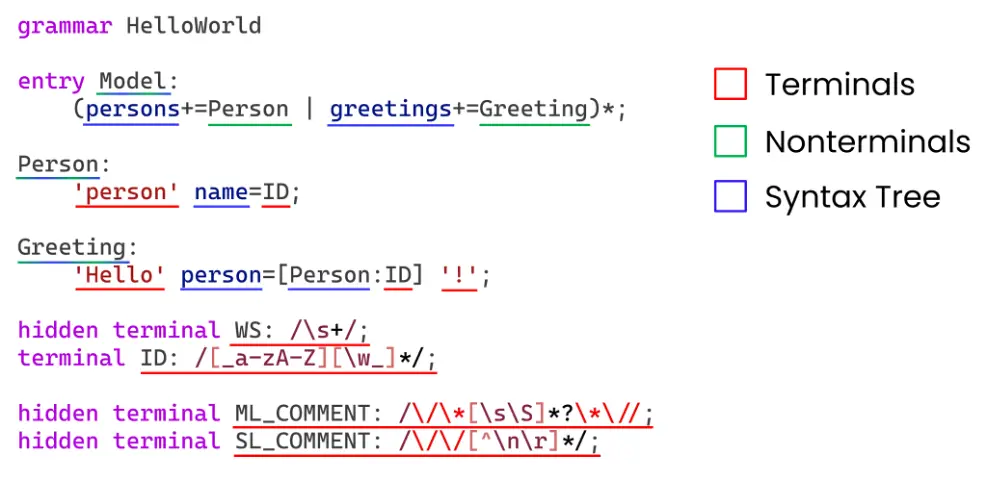

Langium and Xtext come from the same school of thought in language engineering. Both start with a grammar that reads almost the same in both frameworks: you declare the structure of your language, and the framework generates a parser plus the machinery to build an abstract syntax tree (AST). Along the way, they also produce a concrete syntax tree — the CST, or Node Model in Xtext — which records every token, rule application, and text range. The AST holds the semantic structure, the CST preserves the original source, and their connection is what allows the editor to map semantic information back to characters on the screen.

This shared setup explains why both frameworks cover so much ground out of the box. With an AST, a CST, and their cross-links in place, a language server can offer the most common LSP features immediately: completion, definitions, references, folding, and more. This makes the approach especially valuable in the early design phase of a DSL — you get a rich toolchain quickly, without committing to architectural decisions too soon.

The differences lie mostly in the runtime environment and the representation of models. Xtext is a Java framework deeply rooted in the Eclipse ecosystem, using EMF to represent ASTs and to support serialization, cross-referencing, and integration with other modeling technologies. Langium, in contrast, is built with TypeScript and represents AST nodes as plain JavaScript objects. That keeps the runtime lightweight and makes Langium a natural fit for language servers, Node.js-based toolchains, and—importantly—browser-based frontends.

Langium has also evolved some features further than Xtext’s original grammar model, introducing concepts such as multi-references and infix operator rules that simplify the definition of common language patterns. And while both frameworks follow the same conceptual architecture, Langium’s reach extends beyond traditional IDEs into web applications and cloud environments, where modern DSL tooling increasingly lives.

Both Xtext and Langium begin to show familiar stress patterns when we scale up the amount of input to be processed. We’ve seen this across many customer domains: performance issues crop up once user workspaces reach a certain size — often several megabytes — and the frameworks suddenly spend far more time and memory just keeping the model alive. Fixing these issues isn’t straightforward most of the time. Holding a lot of data in memory (ASTs, CSTs, caches) can lead to out-of-memory errors. Putting this data into memory in the first place takes a lot of CPU time. And while parallel processing should help, it isn’t always possible, especially when adding it as an afterthought to the language server or compiler.

Over the years, we’ve used both Xtext and Langium incredibly successfully in all sorts of programming-language projects. But the architectural approach that makes them so productive in the early phases also means they suffer considerably from the issues outlined above. The pain points tend to surface in the same places — but each framework hits them for slightly different reasons.

Xtext’s biggest performance challenge stems from its model representation and the cost of constructing it. While capabilities exist to unload resources, a full workspace build still requires every resource to be loaded at least once, churning through a gigantic amount of memory due to always generating a CST in addition to the AST. In our experience, as much as 80% of the whole memory is consumed by the CST. When projects grow large, this alone is enough to push the system into out-of-memory territory.

Parallel processing in Xtext is also constrained by its reliance on the Eclipse Modeling Framework (EMF), which contains no guarantees for thread-safe access. While this isn’t an issue when building ASTs, it becomes much more of a problem once you start resolving cross-references. As a result, parallelization is possible, but oftentimes quite tricky and requires a deep understanding of when to synchronize threads. Teams that try to speed up processing usually find themselves navigating EMF internals rather than focusing on language logic.

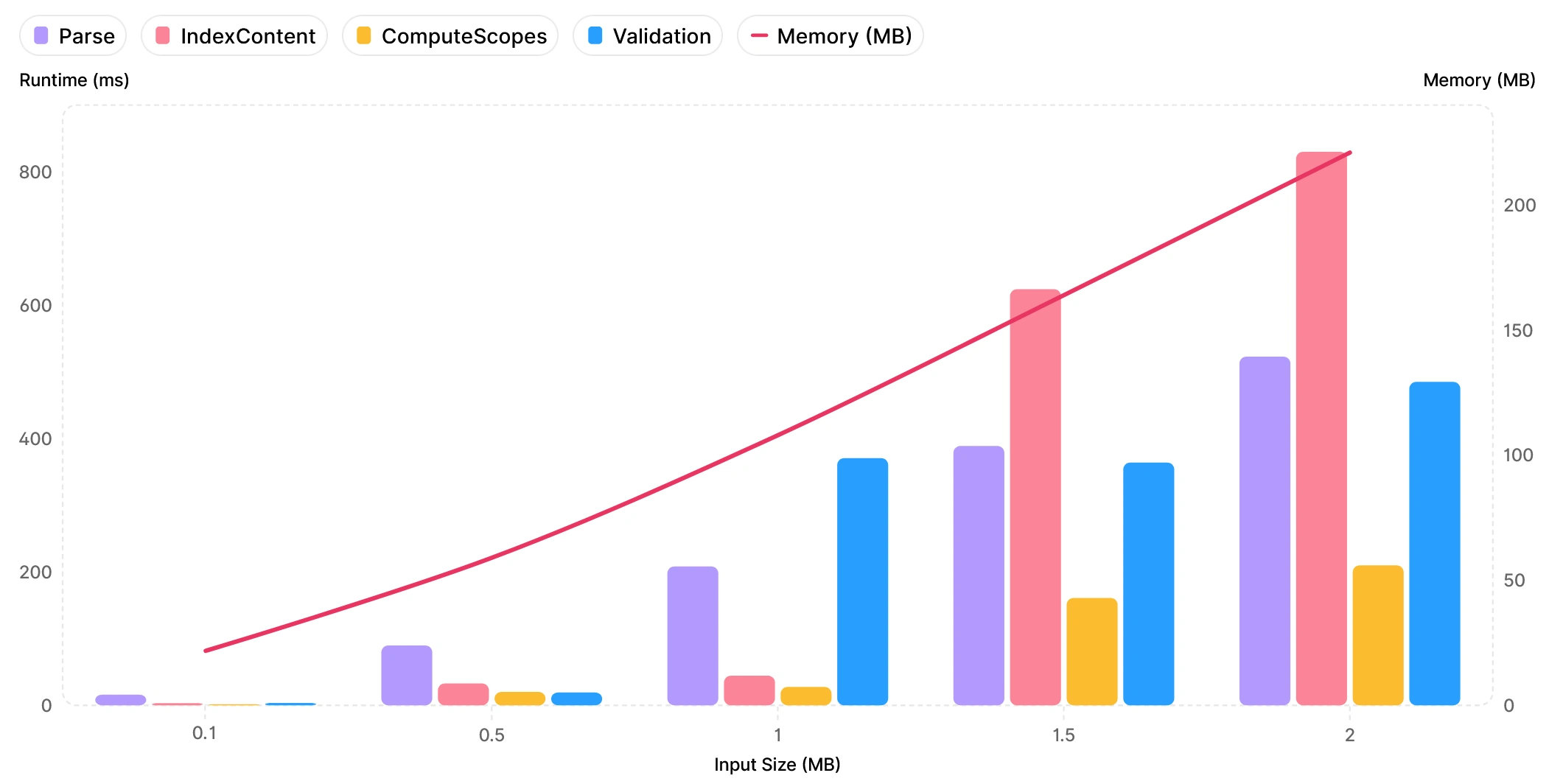

Langium hits similar bottlenecks but for reasons tied to JavaScript runtimes and the design trade-offs of staying lightweight. Similar to Xtext, Langium constructs a CST that roughly takes up 75% of the memory consumed by the framework. This also correlates with the performance problems, as our performance benchmarks indicate that the parser roughly spends 60% of its entire runtime just constructing the CST in memory — a significant cost before any semantic work begins.

Parallel processing is even more difficult compared to Xtext. Since JavaScript runtimes don’t feature a shared-memory parallelization model, other threads cannot simply access the same structures. Even though we made attempts to at least parallelize the parsing, nothing really useful came out of it: the overhead of transmitting large data structures between threads is too large. As a result, heavy parsing loads translate directly to blocking behavior in the language server: since parsing is a blocking process, the server cannot receive any updates from the client during that time. It’s not even possible to abort parsing, because the server cannot be notified that a new change in the file has occurred.

The chart above clearly shows that as input size increases, the run time and memory usage increases mostly linearly. However, at some point for files larger than 1MB, response times of the language server start to degrade into the 1000+ ms range. While files of this size are rare, this effect can be seen in large workspaces as well, although to a lesser degree. This results in a rather sluggish user experience when working on large files or workspaces.

Looking across our experiences with Xtext, Langium, and several custom-built language servers, a few clear learnings stand out. The most important one is that a major share of the overall cost — both in memory and CPU time — comes from constructing and maintaining the full CST. Since the CST is consuming so much memory and CPU time, we should try not to rely on the whole CST structure. While collaborating on the PL/I Language Support of the Zowe project, we’ve already seen what this can unlock: we replaced the CST completely with metadata on the input tokens. This has completely eliminated the overhead of constructing the CST, while still retaining the essential information we need from it. The performance gains in this setup were substantial, and they point clearly toward a different architectural direction.

Another learning relates to parallelization. Language servers should ideally use languages or runtimes that support shared-memory parallelization. And to use parallelization effectively, all its components must be built to support parallelization from scratch. Access to features such as cross-references needs to be performed in a thread-safe manner, and ideally, we should be able to parallelize all stages of the compilation process. Retrofitting parallelism into an existing framework — where data structures and assumptions were never built for it — rarely produces results that move the needle.

These insights also lead to a broader conclusion: the improvements we are talking about cannot simply be bolted onto existing frameworks. They require a new implementation and, with it, a switch to a different runtime platform. That choice alone carries huge consequences and opportunities. It affects how deeply we can leverage parallelism, what memory models are available, and how well the resulting technology fits into the expectations of communities, companies, and individual developers.

At the same time, it’s important to keep the scope of this effort in perspective. Only a small portion of all languages based on Langium and Xtext suffer from the performance problems discussed here. Many DSLs never reach the size or complexity at which these bottlenecks appear, and for them, the existing frameworks remain a great fit. What we need is not a replacement, but a specialized framework for high-performance use cases — one that complements the existing tools rather than competing with them.

All of these learnings have led us to a clear decision. In the first quarter of 2026, we’ll announce a new language engineering toolkit designed specifically for high-performance use cases. After careful consideration, we chose Go as the programming language and platform for this work. Go offers powerful built-in parallelization and synchronization constructs, compiles to OS-native executables, and keeps things generally simple — exactly the combination we need for the next generation of large-scale language tooling. This aligns with the conclusion the TypeScript team reached earlier this year: in March, Microsoft announced their plan to move the TypeScript compiler to a Go-based native implementation to unlock better performance, stronger parallelism, and a more predictable memory profile. Their reasoning resonated strongly with what we’ve observed in our own work.

At the same time, Langium remains our number one choice for most projects, and we will continue investing heavily into its ecosystem. In fact, there will be more announcements about new additions to the Langium family as well.

If you’re interested in the performance topic or want to follow our work on the new toolkit more closely, we’d be happy to talk. Let’s explore the next chapter of language engineering together.

Mark is the driving force behind a lot of TypeFox’s open-source engagement. He leads the development of the Eclipse Langium and Theia IDE projects. Away from his day job, he enjoys bartending and music, is an avid Dungeons & Dragons player, and works as a computer science lecturer at a Hamburg University.

Miro joined TypeFox as a software engineer right after the company was established. Five years later he stepped up as a co-leader and is now eager to shape the future direction and strategy. Miro earned a PhD (Dr.-Ing.) at the University of Kiel and is constantly pursuing innovation about engineering tools.